Lessons on burnout, balance, and human-centred engineering learned through my recovery from a stroke in my thirties.

Listen to this article

Introduction

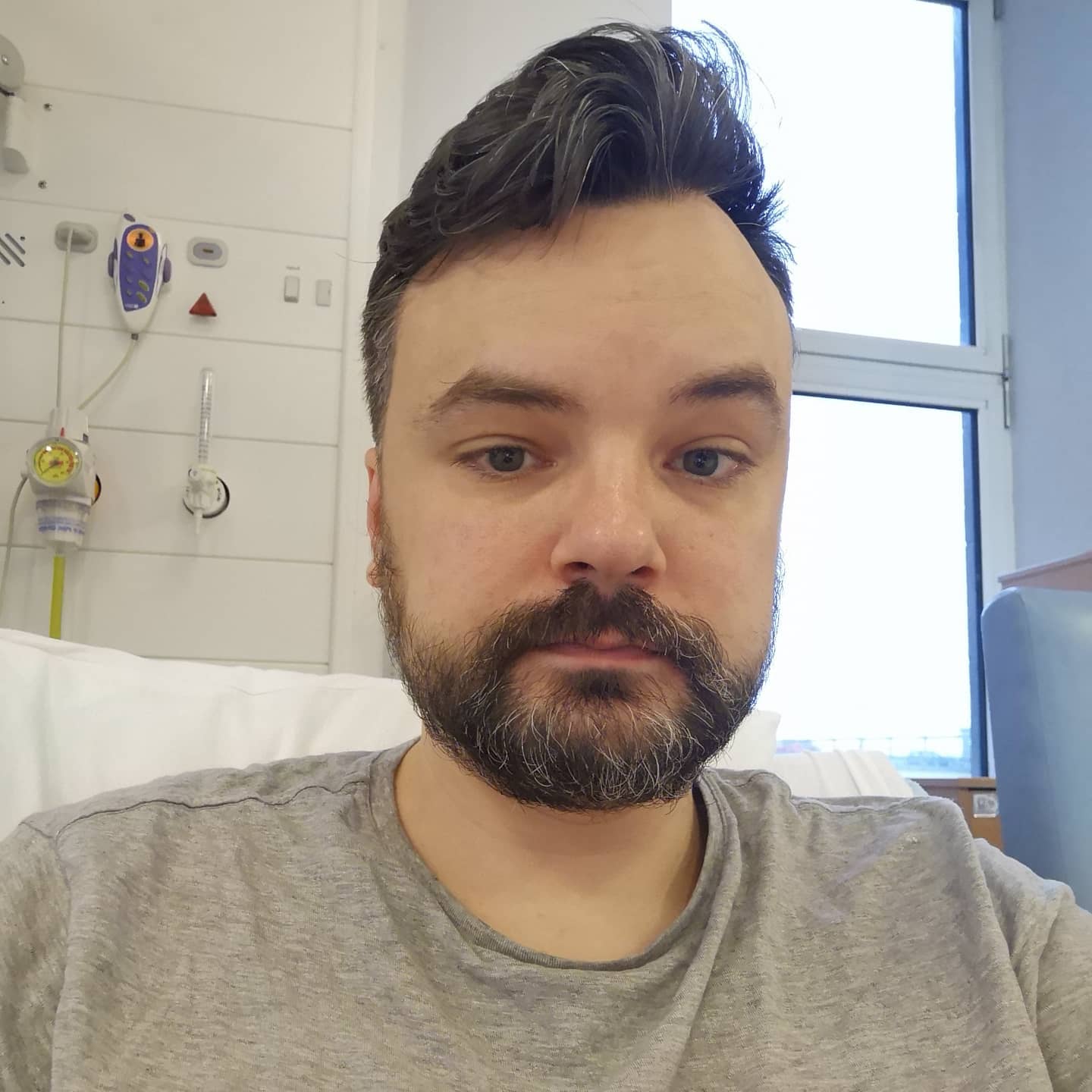

At 34 years old, in the prime of my career, I suffered a stroke.

On 7th October 2021, around 10pm, I was cooking a late dinner and had a sudden sharp pain in my head, followed by vomiting and weakness. Assuming this was a migraine I went to bed and continued my life as normal. When this headache hadn't lifted by the 11th I phoned NHS 111 and was immediately taken to hospital, where it was revealed that sudden pain was in fact a stroke.

I was very lucky. The stroke affected the base of my brain, the cerebellum, which amongst other things controls balance and movement. If the clot had been elsewhere or slightly worse I could have faced instant death or lifelong disability. As it stands it seems I have escaped any significant degradation to my motor skills.

I wasn't sure what the road to full recovery looked like at this point.

I was in a hospital bed grappling with paralysis and uncertainty. Strokes were supposed to happen to older people or the chronically ill, not someone in their thirties. Yet there I was, forced to confront my own fragility.

I'm a Frontend Engineer and design systems specialist with over 15 years in web development. I've built design systems from scratch, scaled frontend architecture for enterprise SaaS products, and led engineering teams through high-pressure fintech launches. I was used to solving complex problems under tight deadlines and prided myself on being the go-to person for all things frontend. But none of that technical expertise prepared me for the challenge of rebuilding my health from the ground up.

Looking back, the warning signs were there. I had been working long hours, immersed in a tech culture that prizes speed and relentless delivery. In many software companies, the pursuit of lightning-fast achievement leads developers to neglect basic needs like rest and mental health. I was no exception. Before my stroke, I regularly pushed through long days fuelled by caffeine and a sense of misplaced duty. I learned I was far from alone – burnout in our industry is at epidemic levels, with a 2021 survey finding that 83% of developers felt overextended or exhausted.1 Tech leaders often celebrate "grind" culture, but rarely talk about its human cost.

Recovering from my health crisis forced me to re-evaluate everything: how I work, how I lead, and how I live. This article isn't just a personal memoir of recovery; it's a set of hard-won insights for frontend engineers, design system practitioners, and engineering leaders. I'll share how surviving burnout and a stroke at 34 redefined my approach to work and life. My hope is that these lessons can help others in tech avoid the mistakes I made and build a healthier, more resilient career in the long run.

The initial shock

The collapse, when it came, felt sudden but was actually years in the making. I remember pushing through a release one week, running on adrenaline and red bulls. The next week, I was at home when I noticed my vision blur and the side of my body go numb. This was a life-threatening event, sprung from what I'd dismissed as "just stress." Only later did I realise how severely chronic stress had been ravaging my body. (Yes, stress isn't just "in your head" – prolonged high stress actually changes your brain and body chemistry, contributing to issues like high blood pressure, inflammation, and ultimately burnout or worse.)2

It's painful to admit, but I had ignored all the warning signs. I treated my body like a machine that could be tuned for peak output indefinitely. In reality, I was a system degrading under constant load – just as any server or application will eventually crash under 100% CPU usage with no downtime. When my body finally gave out, it forced an immediate reboot of my life. Lying in a hospital bed, work was the last thing on my mind. I was facing months of recovery just to get back basic functions. This was the ultimate wake-up call: no deadline or project can ever matter more than your health. If you keep pushing until you break, the cost is unimaginably high.

The experience also opened my eyes to how widespread this problem is. Burnout had felt personal, but it's a systemic issue in tech. We regularly celebrate "hero" developers who pull all-nighters, even though overloading on hours is a surefire path to burnout.3 In hindsight, my stroke was the disastrous climax of a work style that many engineers fall into. I'm sharing this part of the story as a caution: don't wait for a health collapse to confront your burnout. The earlier you recognise it, the easier it is to change course.

Relearning the basics: recovery and patience

Coming out of the hospital, I entered a months-long period of rehab and healing. Starting from the basics. Simple tasks I used to do on autopilot now required tremendous concentration. My brain felt slow, foggy. Typing an email or reading documentation for more than a few minutes left me exhausted. As someone who had always moved fast and juggled complex projects, this was frustrating and humbling. I had to relearn patience in a very literal sense, one day at a time.

In rehabilitation, progress was incremental. Initially, I measured success in very small wins: managing a short walk without fatigue, reading a few pages of a book and actually retaining the information, eventually doing a bit of coding practice to exercise my brain. Just as you can't refactor an entire monolith in one sitting, I couldn't "fix" my cognitive impairments overnight. I had to chip away step by step, trusting that consistency would compound into real results. This experience gave me a new appreciation for incremental progress – in both healing and coding. Whether you're recovering neural pathways or untangling spaghetti code, sustainable improvement comes from iterative, steady work rather than heroic overnight miracles.

In software, when you max out CPU or memory without relief, the system crashes or goes into a safe mode. Likewise, during rehab I learned that pushing myself too hard - mentally or physically - would set me back. My brain literally needed rest periods to rewire itself. In those early months, if I tried to force intense problem-solving or multitasking, I'd hit a wall. I had to respect my cognitive load limits. Interestingly, this made me reflect on my pre-stroke work habits: I often operated at 100% capacity, context-switching between meetings, coding, and emergencies with no downtime. It's no wonder I eventually crashed. Humans and systems both degrade under continuous max load - and both can recover if you dial back the stress and rebuild gradually.

I had firsthand insight into what it's like to struggle with tasks that "should" be easy. Progress isn't linear and everyone has off days. The perfectionism and constant urgency I used to carry were replaced with a focus on steady, sustainable progress. Ironically, by relearning the basics of taking care of myself, I became a better engineer and teammate than I was when I was "high performing" but burnt out.

What it taught me about work/life balance

One of the clearest lessons from my stroke recovery was that rest is not a luxury - it's part of the job. In the past, I saw time off, sleep, and hobbies as things you squeeze in around work. Now I schedule them with the same importance as meetings or coding sessions. Why? Because I learned that my brain is my primary work tool, and it needs regular maintenance. I used to push through fatigue; now I step away, knowing that a fresh mind will often solve in minutes a problem that a fried brain could barely fathom.

I also learned that saying "no" can be the most productive move. Before, I was a chronic over-committer - I'd accept unrealistic timelines, take on emergency tasks late at night, and generally try to be the "yes man" to prove my worth. It nearly killed me. During recovery, I simply couldn't do that - my capacity was limited, and I had to prioritise ruthlessly.

Surprisingly, the world didn't end when I pushed back on requests or asked for more time. Instead, something amazing happened: I found that setting boundaries earned me respect. By diplomatically saying "I can't take this on right now" or "this deadline isn't feasible without risking quality," I opened honest dialogues with my team and managers. We'd re-prioritise or find another way. It turns out that being clear about your limits is healthy for both you and the product. As a bonus, it teaches your team that it's okay to set boundaries of their own.

Human-centred engineering

Before my health crisis, I viewed engineering leadership primarily as shipping features, refining architecture, and mentoring code quality. Those are all important, but my perspective broadened significantly after the stroke. I came to realise that one of the most critical roles of an engineering leader is protecting the humans who build the software. A team that is burnt out, stressed, or unhealthy will eventually grind to a halt, no matter how brilliant the individuals are. Conversely, a team that feels supported and balanced will sustain high performance and creativity. As a leader, it's my job to cultivate the latter and prevent the former.

This human-centred mindset means I think about processes and culture as much as product and code. For instance, I ask myself: Are we setting realistic deadlines that respect weekends and evenings? Do engineers feel safe admitting when they're overwhelmed? Have we normalised taking time off and actually disconnecting? If the answer to any of those is no, I treat it as an urgent problem to solve. Engineering leadership, in my view, must include being a steward of the team's well-being.

Another area I've doubled down on is building systems that reduce stress by design. As a design systems specialist, I've always been passionate about creating reusable components and guidelines to make developers' lives easier. I've become a big proponent of platform engineering - providing internal tools and automation that take cognitive load off engineers. For example, I created a self-service script for spinning up new frontend apps with our design system and CI already configured. This removed a bunch of tedious setup work and the anxiety of "did I configure this right?" for every new project. It's amazing how much stress you can lift from a team by streamlining the boring stuff.

Design systems themselves, when done right, are a huge stress reducer. The goal of a good design system is to make the right thing the easy thing. Instead of every product team reinventing the checkbox or fighting over UX consistency, they can trust a well-documented component library. This cuts down decision fatigue and avoids the tension of last-minute UI inconsistencies. By building and evangelising these systems, I'm not just creating technical assets, I'm fostering a calmer, more predictable engineering environment.

Before my stroke, I was laser-focused on technical excellence: writing clean code, enforcing best practices, optimising for scale, and chasing the latest frameworks. Don't get me wrong - I still value those things highly. But I used to emphasise the what (the output, the product) often at the expense of the how (the process and the people). After my recovery, I view every technical decision through the lens of sustainability. Now I ask: Will this choice make developers' lives easier or harder? Will it reduce cognitive load or add to it? For example, if adopting a new frontend framework adds significant complexity and stress (without a clear benefit), I'm much more likely to say "no" even if it's shiny and trendy. In contrast, I'll champion efforts that improve maintainability or developer experience, even if they don't directly deliver a user-facing feature, because I know those efforts pay off in team well-being and velocity.

Practical takeaways for engineers and leaders

Finally, I want to distill everything I've learned into a few actionable insights. Whether you're an individual contributor or a team lead, here are four key takeaways from my journey:

- Rest is strategic. High performance in software engineering is not about constant grind; it's about smart recovery cycles. Treat sleep, breaks, and time off as essential parts of your workflow - they will make your code and decisions better, not worse.

- Stress compounds silently. Unchecked stress accumulates over time. Don't wait until you hit a wall; start implementing stress-reduction habits at the first warning signs. It's much easier to course-correct early than recover from a total collapse.

- Build sustainable systems. As an engineer or leader, invest in tooling, automation, and processes that make life easier for the team. Automate the painful deploys, document the common patterns, create reusable components - reduce cognitive load wherever possible. The less brainpower wasted on drudgery or uncertainty, the more energy available for creative, fulfilling work.

- Leaders should model balance. If you're in any kind of leadership role (even just as a senior dev mentoring others), know that your team will take cues from you. Modelling work/life balance is one of the most impactful things you can do. When you take care of your health and openly set boundaries, you give others permission to do the same.

Conclusion

Recovering from a stroke at 34 was never part of my career plan, but in hindsight it's been a profound teacher. It brutally highlighted the cost of the unsustainable way I was working, and it gave me the clarity (and frankly, the permission) to realign my priorities. Nothing clarifies what truly matters like a brush with your own mortality.

As engineers, we pride ourselves on building scalable, resilient systems. We design our applications with failure handling, maintenance, and longevity in mind. We should treat our own health with the same foresight and care.

Footnotes

-

ComputerWeekly. "How to prevent developer burnout." 2021. https://www.computerweekly.com/opinion/How-to-prevent-developer-burnout ↩

-

Harvard Health. "Understanding the stress response." 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response ↩

-

Pega F, Náfrádi B, Momen NC, Ujita Y, Streicher KN, Prüss-Üstün AM; Technical Advisory Group; Descatha A, Driscoll T, Fischer FM, Godderis L, Kiiver HM, Li J, Magnusson Hanson LL, Rugulies R, Sørensen K, Woodruff TJ. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000-2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. 2021 Sep;154:106595. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106595. Epub 2021 May 17. PMID: 34011457; PMCID: PMC8204267. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8204267 ↩